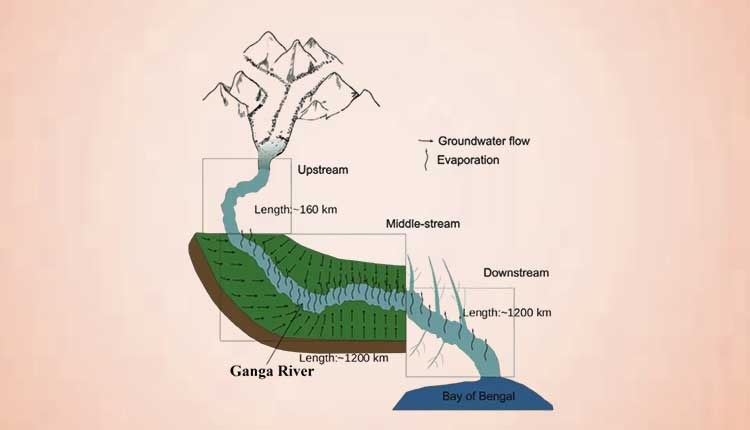

New Delhi: Challenging a long-standing belief, a new study conducted by researchers at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Roorkee has revealed that the Ganga River’s summer flow is primarily maintained by groundwater discharge rather than glacial melt. The findings, published in the journal Hydrological Processes, provide fresh insights into the river’s hydrology and call for a shift in the country’s water conservation strategies.

According to the study, the contribution of underground aquifers enhances the river’s volume by nearly 120 per cent along the middle stretch of the Ganga, particularly during the non-monsoon months. In contrast, the much-feared decline in glacial reserves has a negligible impact on the river’s flow in the Indo-Gangetic plains. The researchers found that beyond the Himalayan foothills, the glacier-fed input is virtually absent up to Patna, after which tributaries such as the Ghaghara and Gandak take over as key contributors.

One of the more alarming revelations of the study is that over 58 per cent of the Ganga’s water is lost to evaporation during the summer—a factor often overlooked in assessments of the river’s health. This significant water loss, the researchers warn, further underlines the urgency of adopting a more nuanced understanding of the river’s water balance.

Professor K.K. Pant, Director of IIT Roorkee, noted that the study marks a turning point in how river conservation policies should be framed. “This research redefines how we understand the Ganga’s summer flow. It provides a scientific basis for designing long-term rejuvenation strategies not just for the Ganga but for other Indian rivers as well,” he said.

Contrary to previous satellite-based studies suggesting rapid groundwater depletion across North India, the IIT Roorkee team found that groundwater levels across the central Ganga plain have remained largely stable. Their conclusions are backed by extensive isotopic analysis carried out along the entire length of the river—from its Himalayan origin to its delta—along with its major tributaries.

Lead researcher Professor Abhayanand Singh Maurya explained that consistent water flow from shallow hand pumps over decades offers strong evidence of a resilient aquifer system. “Our analysis shows that the Ganga is not drying because groundwater is vanishing, but because of human-induced pressures—such as over-extraction, excessive diversion, and the continued neglect of tributaries. Groundwater remains the hidden lifeline of the Ganga,” he said.

The study’s findings highlight the urgent need to rethink water management practices in the region. Researchers argue that reviving tributaries, releasing sufficient environmental flows from barrages, and restoring local water bodies to recharge aquifers must be prioritized to safeguard the river’s future.

As climate variability and increasing water demand put further stress on India’s river systems, this study adds a vital piece to the puzzle of how to preserve the country’s most sacred and economically important waterway.